Click any of the links to jump to a section.

The Early Years – 1784-1812

A New Name – 1812-1845

War and Tradition – 1846-1860

To Save the Union – 1861-1863

The Valley of Death – 1863-1865

Conflict and Expansion – 1866-1898

An Asian Jungle War – 1899-1912

Keeping the Peace – 1912-1921

Hard Times and World War – 1921-1940

The Second Great War – 1941-1946

A Colder War and Vietnam – 1948-1969

Tactical and Ceremonial – 1970-2001

A New Kind of War in a New Millennium – 2001-Present

The Early Years – 1784-1812

The U.S. Army’s oldest infantry regiment, The Old Guard, was created on June 3, 1784 as a result of the 1783 Peace of Paris. The provisions of the treaty ending the war between Great Britain, France, and the colonies of British America (Americans know the war as the American Revolution) was the requirement that the newly independent colonies take military control and civil responsibility for the land west of the Appalachians. This area is now occupied by the states of Ohio, Iowa, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Michigan, and the border along the Great Lakes with British controlled Canada. At the time, Native Americans and their British allies inhabited this region.

The American army that had won the Revolution (with the help of a French army and French fleet) had been largely disbanded and the troops returned to their respective states in the spring of 1784. The Commander-in-Chief bid good-bye to his officers, and returned to his Virginia farm on the Potomac River. A single, small artillery detachment, posted to West Point, was retained from the Continental Army. For practical purposes, there was no force left to defend the United States. Congress was forced, because of the provisions of the Treaty of Paris, to create an army. The single unit created became The Old Guard.

The troops of the new unit, probably not more than 450 men, and the officers, never more than a few dozen in the first years, were the last of the troops from Connecticut, New Jersey and Pennsylvania who were induced to enlist (having first been mustered out of the old Army.) The officers held their commissions from the states from which they came, since there was no legislation authorizing the Confederation of States to issue commissions. These were the beginnings of the national defense and the United States Army.

The Treaty of Paris required that the United States accomplish three missions. First, to receive the garrisons west of the Ohio River held by the British Army, and to garrison some of those forts. Second, to control the flow of settlers (and “squatters”) from the east, a large number of who were claiming lands offered to them in lieu of Continental Army pay long in arrears. And lastly, to attempt to control the inevitable clashes between the Indians and the settlers and land speculators. The force that was created in 1784 to accomplish these missions was called the First American Regiment.

The First American Regiment began to train at a series of forts along the Pennsylvania frontier in the fall of 1784. The first commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Josiah Harmar, began to plan a campaign to subdue the Indians and then force the departure of the British garrisons. His efforts in the next years–and those of other commanders in later years–met with only limited success and two catastrophic defeats–Harmar’s defeat in October 1790 with the First American Regiment and St. Clair’s defeat in November 1791 with the new 2nd Infantry–largely because of tactical mistakes and a weak national government that could not adequately support sustained military operations on the frontiers.

For the first twelve years of the existence of the Regiment, it fought under several names. Created as the First American Regiment in 1784, it was also known as the Regiment of Infantry in 1789, the 1st Infantry after the raising of the 2nd Infantry in 1791, the Infantry of the 1st Sub-Legion of the Legion of the United States in 1792, and again as the 1st Infantry in 1796.

The Legion of the United States was a combined arms organization consisting of highly trained and specialized Infantry, Artillery, and Cavalry. Under the command of Pennsylvanian (and stern disciplinarian) Major General Anthony Wayne, the Legion finally broke the back of Indian resistance to settlement in the Old Northwest at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in August 1794. One eventual outcome of the Battle of Fallen Timbers was that the British were finally forced to surrender Detroit, their last garrison in the United States, in 1796. The mission accomplished, the Legion was broken up and the Regiment again became the 1st Infantry.

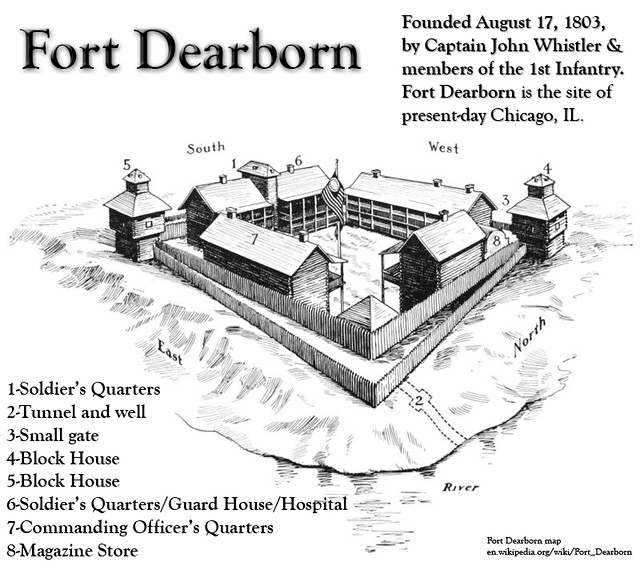

On August 17, 1803, members of the 1st infantry, under CPT John Whistler, established Fort Dearborn. Fort Dearborn was the first permanent military presence in Chicago, IL. In March 1803, the Secretary of War instructed Colonel Hamtramck, commander of the 1st Infantry and commandant of Detroit, to dispatch one officer and six men to survey Chicago. Interest had increased in Chicago, since native tribes withdrew as a result of the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. The positive findings of the survey resulted in construction of Fort Dearborn. The fort, named for the Secretary of War who commissioned it, took one year to complete. Whistler was named commandant of Chicago and remained there until 1810.

A New Name

At the outset of War in America in 1812, the Regiment was sent to the Niagara frontier in New York and points west, participating in the more or less continuous combat in that theater of war, including several attempts to invade British Canada. When peace was declared in 1815, it was largely because the powers of Europe were exhausted by 25 years of war with France and Napoleon. The United States Army returned to a peacetime establishment at the end of the conflict. That peacetime establishment required a force reduction (a “downsizing” in modern terms) of more than thirty regiments in the infantry alone. The forty-six regiments of infantry were, in 1815, consolidated into eight, mostly by combining the troops from five or more regiments into one unit and then re-numbering the surviving organizations. The old (pre-1815) 1st Infantry was the oldest unit used to make up the new (post-1815) 3rd Infantry, which created the direct lineage as the Army’s oldest active infantry unit. The commanders of the new units and their numbers were chosen on the basis of seniority. The first commander of the new 3rd Infantry was Colonel John Miller, previously of the 17th Infantry and third in seniority in the Army. The number of the unit became the “3” as a result of Miller’s seniority.

The westward expansion of the United States during the hundred years after 1784 was not peaceful. Old Guardsmen were engaged in the same exploration, peacemaking, peacekeeping, building, and combat missions as the rest of the Army. The Old Guard was responsible for building many of the forts of the west, some of which became cities as settlement continued. Fort Dearborn eventually became the city of Chicago. Fort Howard contributed to the development of Green Bay, Wisconsin. Jefferson Barracks, Missouri was built in what became the city of St. Louis. In Kansas, the regimental commander, Colonel Henry Leavenworth, chose the site of the fort which bears his name. Camp Supply, Oklahoma, is now a state historic site. Many other posts, forts, or fortifications were built or manned by The Old Guard.

After the war of 1812, many of the traditional patterns of Army life in the west, and many of the traditional missions of the Regular Army in American life began to be evident. Serving on the frontiers, the Army built most of its own posts, most sized for only a few companies operating independently of their regimental headquarters. As the only body of men under the control of the government with a clear mandate to use force to implement the national program of resettlement of the Indians, the Army was central to the policy of gaining military control while protecting the Indians from unscrupulous or terrified settlers. One of the most difficult of these situations concerned the Republic of Texas, its border with the United States, and the adjacent Indian Territory. Through the 1820’s and 1830’s, The Old Guard was stationed in Louisiana, Arkansas and Missouri, guarding in depth the border with the Texas Republic and the Indian Territory.

In April 1840 the entire 3rd Infantry Regiment, numbering around 690 men, was sent to Florida to participate in the war against the Seminole Indians. The three-year conflict ended by negotiation in time for the Regiment to be sent again to St. Louis as instructors and demonstration troops in the School for Brigade Drill at Jefferson Barracks in 1843. It was during this period that the first recorded instance occurred of the Regiment earning the nickname “buff sticks,” after a flat stick of wood with a soft piece of leather attached that was commonly used to shine metal buttons and other uniform parts. In 1844, the Regiment moved again to the Texas border, to Louisiana as part of the “Army of Observation,” protecting the border from the Texans and Mexicans. On the border, the Regulars created “Camps of Instruction” to increase the level of combat readiness of the Army as a whole. They were soon to need it.

War and Tradition

The war with Mexico, which began as a result of the admission of Texas to the union in 1846, is not well remembered today. It was, in its time, an unpopular war conducted by American armies invading Mexico from the north and east. Always outnumbered, operating without secure supply lines after amphibious landings in a foreign, armed and hostile country, the American troops found their enemy entrenched and fortified in his own cities and towns, with weapons equal or superior in quality to their own. Most serious military observers expected the Americans to be beaten by the Mexican Army of Santa Anna. American supply lines were considered to be too long and difficult to maintain, and the overwhelming numbers of the Mexican Army appeared to be, before the war began, a telling precursor of disaster. The US victory became an example used to teach and inspire in the American army for generations and the war a training ground for the senior officers of our own Civil War. Success in the face of such overwhelming odds explains why the war has such a central part in the heraldry and traditions of The Old Guard and other Regular regiments.

There were two major campaigns in the sixteen-month war, and the 3rd Infantry played a vital role in both of them. Led by Major General Zachary Taylor, the northern invasion that began the war, after the Mexican attack on American forces at Palo Alto, Texas and Resaca de la Palma in 1846, culminated for The Old Guard in the attack and capture of the Mexican city of Monterey, 130 miles from the border. On the 21st of September 1846, the 3rd Infantry, 262 men strong, was part of the first wave to attack the city. Enemy artillery was stationed at street intersections, and the narrow streets were bounded on each side with buildings filled with infantry. In penetrating the first line of defense of the walled city, the Regiment found itself drawn into a situation in which the limited space to maneuver made it difficult for American units to support each other. The losses that ensued reflect the nature of the combat. Over forty enlisted men were casualties; five officers, including the three senior officers, were killed and five wounded. The unit took its objective and held its ground until a lack of ammunition made withdrawal a necessity. Even the Regiment remained under Mexican artillery fire during the night and into the morning, when the city fell to the American army. The bitter house-to-house defense of the city by the Mexican troops made it the most costly single day in the history of the 3rd Infantry before Gettysburg. The anniversary of that day in battle was chosen in 1920 as the unit’s Organization Day.

The southern campaign of the war began in December 1846. The 3rd Infantry was transferred to a force under the command of Major General Winfield Scott. His campaign began formally on March 9, 1847 when General Scott’s army participated in the first large-scale amphibious landing ever undertaken by the U.S. Army, at Vera Cruz on the eastern coast of Mexico. The 3rd Infantry, among the first ashore, helped to secure the city, which was the anchor of the American supply line for the campaign on the Mexican capital. It is in this campaign that many more of the traditions of the Regiment were born, enduring to be recognized officially almost a century later.

From Vera Cruz, the Army made straight for Mexico City. The Old Guard fought during the campaign as part of the Brigade of Regulars, the 1st Brigade of the 2nd Division. The first resistance was at Cerro Gordo in April 1847, a small, crossroads town, overlooked by hills. The fight for the heights, especially Telegraph Hill, would create another regimental tradition.

The heights of Cerro Gordo were occupied by Mexican artillery and though the Americans had artillery positions that could bombard the hill their only means of driving the enemy off was a direct assault. Common to the tactics of the day (the tactical manual had been written by General Scott) was close order volleying followed by a bayonet charge, undertaken as the best and fastest way to cover the ground to an objective and grapple decisively with an enemy. General Scott wrote of the assault that:

“…the style of execution which I had pleasure to witness, was brilliant and decisive. The brigade ascended …without shelter, and under the tremendous fire of artillery and muskets . . . [they] drove the enemy from [the breastworks] . . . and after some minutes of sharp firing, finished the conquest with the bayonet . . .”

A long tradition in European and American armies is a show of subservience to the civil authorities, recognized by marching in peacetime under arms without bayonets fixed–thereby not ready to attack or threaten–and to keep colors covered except in sight of the enemy in time of war. The 3rd Infantry, after verifying with the War Department the facts of the bayonet assault at Cerro Gordo, established in 1922 the Regimental custom of passing in review with bayonets fixed. This practice commemorates the bayonet assault that the Regiment undertook with the 7th Infantry up Telegraph Hill at Cerro Gordo.

The battles of Cerro Gordo (April 18), Contreras (August 19-20), and Churubusco (August 20) were fought on the march to the Mexican capital. Bayonet charges at Cerro Gordo and the desperate hand-to-hand fighting at Churubusco taught that the Mexican troops could not hold against the determined North Americans properly supported. Mexico City, the objective, was a walled city, defended in depth by means of outlying fortifications and fortified buildings, some of which could be reached only by elevated causeways cut at intervals by heavily defended gates and other strong points. Among the last of these fortified places to be taken was Chapultepec, the military academy of Mexico. A fortress sited atop a steep hill, the only approach was a causeway defended by artillery and infantry. Further fortifications surrounded the fortress on level ground. In the final assault of the Brigade of Regulars on September 13, 1847 troops of the 3rd Infantry stormed the walls, raising the American flag on the parapet and establishing a foothold in the fortress which could be exploited. This was accomplished with yet another bayonet charge, which demoralized the defenders of Chapultepec so that most of the Mexican troops soon surrendered. One unit did not. The Cadets of the academy were surrounded. Some fought to their deaths or threw themselves off the parapets rather than surrender, creating an enduring Mexican military tradition to parallel that of the 3rd Infantry.

The next day, the 3rd Infantry had the honor of marching at the head of the brigade as the lead element in the review of American troops as it entered the Mexican capital. It was at this time that the Regiment is said to have received its greatest legacy of the war. The Army commander, Major General Scott, in what is perhaps the greatest praise he could have given, is said to have turned to his staff as the 3rd Infantry passed and said, “Gentlemen, take off your hats to the Old Guard of the Army.” His purported remark, first officially used eighty years later, gave the Regiment its modern (and now official) traditional name.

The regimental collection contains a single artifact of the event, a bandmaster’s baton presented to the Regiment by Brigadier General Persifor Smith, the commander of the brigade in which they fought. Made of wood from the flagpole in the plaza in Mexico City, and mounted in Mexican silver, a story is told that it was a replacement for one broken in the assault. The Chapultepec Baton is the Regiment’s most important symbol, exhibited proudly in The Old Guard Museum.

The war in Texas and New Mexico against the Navajo and Apache was the next duty of the Regiment, and ten years was spent at it. Only a few anecdotes of the period survive, but they provide a diverse look at the life of the men in the Regiment. The first known concert by the Regimental Band, in El Paso, Texas, was in 1850. The story is also told of the march of the Regiment from one post to another in Texas that was interrupted by flash flooding which, because it occurred at night, carried away the camp and drowned a member of the senior NCO staff. The only baggage recovered was a chest of muskets found 20 feet up in a tree about 20 miles further downstream. The Regimental Headquarters and several companies were attacked at night in the summer of 1860 at Fort Defiance, New Mexico Territory. In one of the few Indian assaults against a fortified post on record, men of the 3rd Infantry, fought all night against repeated assaults and defeated the Navajo by dawn.

To Save the Union

The Civil War began in the summer of 1861. In the spring President Lincoln had called for troops to defend the capital and the union, and the Regular Army was expected to set the example for citizen soldiers. The Regiment left Fort Clark, Texas and marched southeast to meet transports, which would carry five companies and the headquarters north, and two companies to Florida to garrison Fort Pickens (April 1861-April 1862).

Companies C & E of the 3rd Infantry Regiment were part of the forces manning Fort Pickens, having deployed from Fort Hamilton, NY and arrived in Pensacola on April 16, 1861. Just after midnight on October 9, 1861, Confederate BG Richard Anderson landed two steamers full of troops on Santa Rosa Island, the 40-mile barrier island on which Fort Pickens is located. His 1200 men attacked soldiers of the 6th New York Infantry Regiment, who were encamped about one mile east of the fort. The New York Regiment was routed and fell back until reinforcements from the fort could stop the Confederate advance. The Confederates took a defensive stance, eventually falling back and leaving Santa Rosa Island. The battle saw 1800 men engaged in battle, with 150 casualities and losses.

Three companies were not able to complete their evacuation of Texas, and were forced to surrender. It was not until the spring of 1862 that the companies from Florida rejoined the Regiment, and shortly after, the attrition and casualties of the first year of the war forced four companies to be disbanded and the men to be distributed to the remaining six. The Old Guard spent the rest of the war as a battalion of six companies. Many of the officers were detached and performed staff duty at brigade and division levels, setting an example in Army administration as the nation struggled to form a successful army. The senior officer, for a time, was Captain George Sykes of Company K.

In July of 1861, the Union advance into Virginia was stopped at Bull Run as the two armies groped and floundered into each other. When the Federal line broke in the afternoon, and the routed army began to flee toward Washington, a movement by the southerners threatened to cut off the retreat. George Sykes, (now Major) with five companies of the 3rd Infantry, two companies of the 2nd, and one company of the 8th Infantry marched his ad hoc battalion to a critical ridge near the road to Stone Bridge. For the only time in the war, the battalion formed a square and successfully defended the ridge and road against infantry, artillery and cavalry until all units of the fleeing army had crossed the bridge. The Battalion then retired in good order to Washington. Fewer than five hundred men had saved the Army and perhaps the union. When the President came to review the troops at the end of the month, the Army commander pointed out the little Battalion and said to Lincoln “these are the men who saved your army.” Lincoln replied “Yes, I have heard of them.”

There was no further combat by Old Guardsmen in Virginia until June of 1862. The Federal movement up the Virginia Peninsula toward Richmond was repulsed in the Seven Days Battles. At Gaines Mill, while holding the Federal right, the 3rd Infantry was attacked by overwhelming forces and stood its ground to save the line from collapsing. The line was held, but at great cost to the Regiment, including the death of the regimental commander, Major Nathan Rossell, who was the last field grade officer to serve with the unit until the end of the war. The rise in the ground where the combat took place is now called Regular’s Hill.

The Old Guard was in heavy combat during the battle of Second Bull Run in August 1862, with The Old Guard deployed as skirmishers in Groveton, and then falling back to hold Henry House Hill. The Old Guard had little part to play at Antietam in September 1862, but was deployed at a potentially critical point. At Fredericksburg, in December 1862, the Brigade of Regulars was used to hold the town below the heights and the 3rd Infantry was posted in a tannery. Under continuous shelling, the Regulars were finally deployed in support of the retreat and were the last troops to return to Falmouth Heights on the north side of the river.

After the defeat at Fredericksburg, the Army’s new commander took action to boost morale and foster esprit de corps. Major General Joseph Hooker reorganized the Army and gave each unit down to division level its own insignia, based on the insignia of its parent Army corps (soldiers already wore a company letter and a regimental number). The system figures prominently in the heraldry of The Old Guard. The white Maltese cross was worn by all men of the 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, of the Fifth Corps, known as the Regular Division. It is the origin of the three crosses on the Coat of Arms of The Old Guard.

At Chancellorsville in May 1863, the initial success of the deployment to the battlefield was followed by an attack east along the Orange Turnpike spearheaded by The Old Guard and the Regular Division. The successful attack was not adequately supported, and the Division withdrew to the Chancellor house. As the day wore on, the Division was sent to secure all of the roads north of Chancellorsville to deny them to the enemy and ensure that the line of communications was kept open. When, after Jackson’s attack, the line of communications became a line of retreat, the Army passed through the Fifth Corps elements and recrossed the river. The Regulars fought the rear-guard action, slowing down the pursuing enemy until the Army could successfully return to the north side of the Rappahannock River.

George Sykes, until Chancellorsville the Division commander–the most common term for the Regular Division was “Sykes’s Regulars”–was promoted to Fifth Corps Commander. He, along with two others (William Penrose and William Hoffman) were 3rd Infantry officers before the war who achieved the rank of Major General. Both Sykes and Penrose had been company commanders in 1860; Hoffman, much older, had been the regimental commander. Command of the Regular Division fell to Romeyn Ayres for the remainder of the war.

The command of the Regiment changed again in the days before the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg. John Wilkins, senior Captain and commander since the death of Major Nathan Rossell at Gaines Mill, was ranked by Captain Henry Freedly, whose parole from his capture in Texas had expired, allowing him to return to active duty. The Regiment entered the campaign as combat ready as any in the division. To a man, they were experienced veterans. Its single shortfall was manpower. More than fifty percent of its officer positions were vacant, and, its six companies–with an authorized strength of 576–had fewer than 300 men present for duty. The casualties and other losses of the Regiment were never replaced.

The Valley of Death

The campaign leading to Gettysburg was essentially a race between armies. When the troops finally blundered into each other–some of the southerners simply looking for shoes–there ensued a series of holding actions until the main bodies of the armies could be brought up to the town and deployed. The Federal line was along a ridge, in the shape of a fishhook, called Cemetery Ridge. At the south end of the line were two hills, Little Round Top and Round Top. That end of the line faced a small valley–called Plum Run Valley–across which was a rocky outcropping called Devil’s Den. North of that, behind a fence, was the Rose Farm, a wheatfield, and a road perpendicular to the Round Tops. It was the single most critical piece of land on the south end of the battlefield, because control of the hills determined who could control the battlefield.

The Regular Division, 3rd Infantry included, reached Gettysburg at 12:30 am on July 2, 1863, the second day of the battle, having marched from Falmouth Heights, facing Fredericksburg, in 30 days (including detours to attempt to capture Confederate Colonel John Mosby) by way of the old battlefield at Manassas and the passes to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. In the previous week there had been but one cooked meal. Reveille was at 3 am. There was no breakfast. They formed at the right end of the Federal line–near Wolf’s Hill–to defend against an assault by Confederate General Ewell’s Corps, which did not occur. Withdrawn to the rear, the Regulars were held in reserve at the center of the Federal line until early afternoon.

During the day, the Federal Third Corps had moved forward of the Cemetery Ridge line to gain and hold a road. The movement had not been coordinated, and by mid-afternoon the Corps formed a salient in the line. The attack of Confederate General Longstreet’s Corps, beginning at 4:00 pm, was intended to take control of the Round Tops, smash into the exposed Third Corps line on the Wheatfield Road, and begin to roll up the Federal line on itself along Cemetery Ridge. The attack was stopped by a handful of infantry and artillery on Little Round Top and the Regular Division in Plum Run Valley and the Rose Farm.

The Regular Division received orders to move at 5 pm, and was sent running to Little Round Top, deploying along the north slope. At about 6 pm, the Division was ordered forward through Plum Run Valley to support the Third Corps troops being pushed out of the Rose Farm and the Wheatfield, and forming a strong point to hold the road. Once they had gained the stone wall, driving off its defenders, the lead elements of the Division and all that followed could not move forward without becoming intermingled with other Federal troops being forced from the field across their front. The Regular Brigades were ordered to lie down in their ranks behind the wall–extending back across to an open ridge–which provided some concealment, a smaller target, and helped to avoid casualties from stray rounds. But they were forced to endure Confederate fire (Benning’s Georgians) from Devil’s Den on their left. At 6:30 pm, the Regulars of the 2nd Brigade moved across the wall in formation, colors flying, wheeled to their left, and began to attack the Confederate forces streaming out of the woods. 1st Brigade, including The Old Guard, held the high ground some yards behind the wall. The 3rd US anchored the line with the Regiment’s right flank open on the road at the right of the Brigade line.

The Regular’s attack caused the Confederates to send reinforcements. When they came streaming down the road and into the wheat field, flanking and engulfing the 2nd Regular Brigade, the pressure at the wall and on the undefended road was too great. The two Regular Brigades were ordered to retire to their old position at the base of Little Round Top.

The Regulars had to fight their way out. The remains of the 2nd Brigade passed through the 1st, and both formed into line of battle–under fire–dressed their lines, and began to slowly and grudgingly give up the ground they had crossed less than an hour before. The muddy, rock strewn ground between the hill and the base of Little Round Top was given up only slowly, as the Regulars delivered perfectly timed crashing volleys into the southerner’s disordered lines. The Confederate assault ground to a halt.

The 3rd Infantry, having the most forward position of the 1st Brigade in the advance, had become the most exposed in the retreat, and was the last to leave the field. When artillery support was brought up to the base of Little Round Top to help slow the Confederate advance and try to save the two Regular Brigades, some elements of the Regiment were caught in the open. Lieutenant John H. Page, who survived to become the regimental commander before his retirement in 1910, wrote later that:

“As we were falling back, we saw the battery officers at the base of [Little Round Top] waving their hats for us to hurry up. We realized that they wished to use canister, so took up the double quick. As I was crossing the swampy ground, Captain Freedly…was shot in the leg, fell against me, and knocked me down. When I got the mud out of my eyes, I saw the artillery men waving their hats to lie low. I got behind a boulder with a number of my men when the battery opened. The Rebels came from all directions for the guns…. They waved their battle flags, a dozen being just in front of me [ie., in his line of retreat, between Page and the base of Little Round Top]. A number [of the enemy] were shot down where we were; they then retreated through the wheatfield and the woods.”

The end of the Regular Division was described by an eyewitness:

“The Regulars fought with determined skill and bravely for nearly an hour, then reluctantly fell back as if on drill, but sharply and bravely contesting every foot of ground. These things I saw, and I am glad, as a volunteer, to bear tribute to the United States Regulars.”

By the time the 3rd Infantry reformed and it and the 1st Brigade watched darkness fall, the men were able to cook their first hot meal in a week. The losses in killed and wounded would never be made up. Of 300 men present for duty in The Old Guard, including only 12 officers, 74 were killed, wounded, or missing, almost 25 percent of the unit. The Old Guard had lost two commanding officers in as many hours. The price paid to stop the assault of Longstreet’s Corps was even higher in other Regular regiments. The real importance of the sacrifice was that the failure of the Confederate attack, blunted on the Regulars, induced the Confederates to attack the center of the Federal line the next day. Losses in Pickett’s Confederate Division were even higher than the Regulars. The loss of the battle ended any real Southern hope of winning the war.

The Regular Division, now little more than just a brigade in strength, was to get no rest. By the middle of August, the Regulars, including the 3rd Infantry, were sent north to New York City.

The conscription of men for service in the Army in 1863 was a new event in American history. Begun just after Gettysburg, it was soon followed by protests everywhere and riots in Ohio, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. The worst of these took place in New York City. Regulars, not subject to the whims of state politics, were sent to quell the riots and enforce the law.

The 3rd, with the rest of the 1st Brigade, moved into the lawless areas of the city still wearing the uniforms that they had worn since camped on Falmouth Heights in May. Several days of fighting occurred at barricades in the streets and at buildings fortified by the rioters. In the end, they were no match for the Regulars, who were neither inclined nor induced to show much mercy to those who refused to serve in the Army. Finally camped at Washington Park and issued new uniforms–and with the East River handy for bathing–their ragged appearance was soon improved, and they began to enjoy a well-deserved rest.

The combat effectiveness of the Regular Division was gone, and it was reduced in size to a brigade, leaving a small number of regiments to garrison New York harbor. The rest, including the 3rd Infantry, returned to Virginia in September 1863, where it participated in operations until December, when the Regiment was transferred to Fort Hamilton, New York. At the beginning of the winter of 1864, Captain Andrew Sheridan, commanding the 3rd Infantry, sent the following letter to the Adjutant General of the Army:

“I have the honor to apply for the relief of the Third US Infantry…from duty in the field and an assignment to some post where they can recuperate and if practicable, recruit. The Third Infantry, after the trouble in Texas in which three companies and many officers were taken prisoners, have been constantly in the field. Ten companies have been consolidated into six, and the effective command now consists of eight officers (three of whom are now Field & Staff and five upon line duty) and one hundred and fifty-eight rifles.”

In October 1864, the Regiment moved to Camp Relief, on the northern outskirts of Washington, DC where the unit performed garrison duties in the city. In February 1865 the 3rd was ordered to join the 4th Infantry as General Meade’s headquarters escort for the Army of the Potomac. The unit served in that capacity for the last three months of the war, and was present at the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox Court House, Virginia in April 1865. The arrangement as General Meade’s escort was made by John Wilkins, commander of the 3rd after the death of Major Rossell in 1862. Wilkins’ made the first known written reference to the 3rd Infantry as an “Old Guard.” In the period of martial law that followed Lincoln’s assassination, the 3rd was retained for in Washington as Provost Guard, and was the lead element in the Grand Review of the Army for President Andrew Johnson. The Regiment that had saved the Army at Bull Run participated in the last act of the war.

Conflict and Expansion

By the spring of 1866, the Regiment was in Kansas. Slowly being recruited back up to strength with men from the eastern cities, the veteran officers (many of them senior NCO’s promoted during the war) had their hands full teaching their men an almost forgotten skill, that of fighting Indians, and peacekeeping (or peacemaking). The Regiment found itself in the old mold of garrisoning dispersed posts and strong points, this time along the Smokey Hill and Santa Fe trails. The Indian War, which began in 1866 in Kansas, lasted eight years. During this conflict two Medals of Honor were won by men of the Regiment in short, sharp fights between small groups of Indians and even smaller groups of soldiers. The Regiment again began to leave the names of Old Guardsmen on the landscape, contributing Beecher’s Island in what is now Colorado, named for Lieutenant Frederick Beecher, killed there in 1868, and building Camp Supply, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), and bringing a veneer of civilization to places like Dodge City and Ellsworth, Kansas. Once the war was successfully concluded, (by 1874 the unit had been on the frontier for eight continuous years) The Old Guard was sent to the deep South for its turn in the occupation of the defeated states of the Confederacy. It was the last of the regiments sent south on that duty, for the mission ended with the end of “reconstruction” in 1877.

After a short period of riot duty in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania during labor unrest in 1877, the Regiment was again sent west, this time to Montana. Here the Regiment became proficient in cold weather operations, and participated in the last significant (Ghost Dance) campaign against the Sioux and their allies. They were called upon to follow (and then to feed) the returning followers of Nez Perce leader Chief Joseph after his unsuccessful flight to Canada. During this period, life in the Regiment was becoming a little easier, and the civilized aspects of army life–wives and families, regular band concerts with the regimental band–began to be more evident. The regimental adjutant, Lieutenant Francis Roe, induced John Philip Sousa to write and dedicate “The Rifle Regiment March” to the 3rd Infantry, and even enlisted an Italian friend of Sousa as 3rd Infantry bandmaster.

In 1888 the Regiment began a long association with Fort Snelling, Minnesota, when it was transferred to that place. It was to settle into its first long-term relationship with civilization, being only occasionally required to send a company to quell a civil disturbance in the area. The mission of the Regiment was modified to revert to an old and honored one for regulars. In summer camps set up to train National Guard troops, Old Guardsmen found themselves as drillmasters, marksmanship instructors, and demonstration troops. As the Northern states began to fill with settlers, more and more of the recruits in the Regiment came from the areas settled by immigrants from Northern Europe. The Regiment began to be considered a part of the community and eventually to be known as “Minnesota’s Own”, a nickname it was to keep for fifty years.

War with Spain, which was declared in April 1898, was not entirely expected, and the country was not prepared. Troops were called to southern areas of the United States and held for training and later transport to Cuba, including the 3rd Infantry which left Fort Snelling in April. The Regiment disembarked in Cuba in June. The war itself was short and sharp, with serious ground combat limited to the American envelopment and siege of the Cuban city of Santiago. In July 1898, the Regiment played a significant part in the Santiago Campaign, enduring tropical heat in woolen uniforms while storming a fortified blockhouse at El Caney that controlled a part of the city’s water supply, followed by three days of more or less continuous shelling in trenches before the city until a ceasefire was signed. After redeploying from Cuba and arriving back in the United States in August, the Regiment was held in quarantine in a camp on Long Island, New York before being allowed to entrain for Minnesota in September.

Just two weeks after the Regiment’s return to Fort Snelling, The Old Guard was involved in the last combat between an Army unit and Native Americans. A group of Chippewa at the reservation at Leech Lake, Minnesota, were being cheated by local white residents of the revenue derived from the sale of timber on the reservation. An argument ensued, and the local U.S. Marshal was summoned, only to be forcefully ejected from the reservation by the Indians, now armed. A company of the 3rd was sent to settle the disturbance in October 1898, commanded by Brevet Major James Wilkinson and Lieutenant Tenney Ross, the former a seasoned veteran of the Civil War and campaigns against Indians for thirty years. The Indians kept the company pinned down by well directed sniper fire for almost three days until it was reinforced. Wilkinson and several of the recruits who had only recently joined the Regiment to fight in Cuba were killed, and ten were wounded. In ministering to the latter, a soldier of the Regiment (in the Hospital Corps) earned the third Medal of Honor awarded to an Old Guardsman.

An Asian Jungle War

In February 1899, the 3rd Infantry embarked for the Philippines, taking a ship of the new US Army Transport Service through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal, arriving in Manila in March. Engaged in combat within three days, they were to stay in the Philippines for three years.

As a result of the war with Spain, the United States had inherited control of the former Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean and the Philippine Islands in the Western Pacific. In the latter place, there had been combat against the Spanish, and Philippine “Insurrectos,” most uniformed and officered in units modeled on European armies, had been a significant contributor to the defeat of the Spanish in their country. They intended, as a result of their victory, to set up an independent, sovereign Philippine government. Aside from the strategic issues of supply depots in the western Pacific for an American Navy dependent on coal, most Americans believed that they should govern the islands so recently paid for in American blood, and the United States took action to set up a colonial administration. The result was war between the United States and the Philippine nationalists for control of the capital (Manila) and the surrounding area. The US Army, Regulars and Volunteers, became involved in its first Asian jungle war.

The nature of the war was different in context but not in practice from the duty the Regiment had seen in Kansas thirty years earlier. Patrolling out of garrisons in the larger towns, and manning outposts in smaller villages, the Regiment fought to break up concentrations of the Insurrectos when they could be found, fought off attacks on its posts and road movements, and engaged in “search and destroy” missions to find and fight an elusive enemy. There were few prisoners taken by either side, (a popular song of the day ran “Beneath the starry flag, we’ll civilize them with a Krag”) and many Old Guardsmen learned a grudging respect for the Filipino and his weapon and tool of choice–the bolo. After three years, the administration, Army, and the Regiment won the battle for the “hearts and minds” of the people in the area, and the Philippines remained firmly in American control for fifty years.

The Regiment returned to the United States in April 1902, to be stationed in Kentucky and Ohio. While the Regiment had been engaged in the war in Cuba and the Philippines, gold had been found in the Alaska Territory, and the influx of people, as well as some concern for the defense of the area because of the Russo-Japanese War, resulted in the Regiment being moved to widely dispersed posts in central and southern Alaska. The Regiment left San Francisco aboard the US Army Transport “Buford” on July 1, 1904 and sailed to Skagway, arriving on July 7. Camp Skagway served as home base until September 1904, when Fort William H. Seward was completed and ready for garrison troops. On September 30, 1904, the Headquarters, Field and Staff elements of the 3d Infantry Regiment left Camp Skagway, Alaska and arrived at nearby Fort William H. Seward, AK. Soldiers of the Old Guard became the first garrison troops at newly-completed Fort William H. Seward, current day site of Haines, AK.

The Regiment often worked broken up by companies and detachments. In addition to Fort William H. Seward and Camp Skagway, the men of the Old Guard were posted to Forts Liscum, Davis, Egbert, Gibbon, and St. Michael. Operating independently in all weather, companies of the Regiment cleared land and strung wire for the military telegraph which, provided communications for these areas. It was unremitting, thankless work, requiring continuous maintenance of miles of wire across land of great beauty and danger. The Regiment was also called to assist in keeping order during natural disasters and in areas where there were no civil authorities. In September 1906, the Regiment left the territory, taking up station at Forts Lawton and Wright in western Washington State, where, for the first time in two years, men were re-united with their families.

In August 1909, the 3rd Infantry returned to the Philippines, to the Island of Mindanao in the extreme south of the archipelago. The inhabitants of the island had rebelled against the government in Manila several times in previous years over a series of ethnic, cultural, and religion-based disputes. Most people of the island are Muslims, tied culturally to the people of Malaya, with whom they share their religion, weapons, and political and social customs. A significant problem was piracy, forcing the Regiment to learn small unit amphibious operations. Another three-year campaign ensued with the Regiment headquartered at Zamboanga, the provincial capital. The three battalions of The Old Guard found themselves again in an environment of more or less continuous patrolling and small unit operations, punctuated by civil actions, public works construction, and quarantine duty. Combat at the town of Jolo in 1911 earned a campaign credit. Operations took place in jungle without roads or trails, described as “the most difficult terrain in the Philippines.” The Regiment returned to the US from the Philippines in 1912 to be stationed at Madison Barracks and Fort Ontario, New York.

Keeping the Peace

After three years in the more civilized area of New York State–and reunion with families not seen for three years–the 3rd was ordered to the border with Mexico in Texas. War in Europe and an unstable political situation in Mexico were the reasons, spurred on by an attack on the town of Columbus, New Mexico, by the irregular Mexican troops of Pancho Villa. This led to a US action in Mexico led by General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing that came to be called the “Punitive Expedition.” Some troops, including the 3rd Infantry, remained on the border. When the United States decided to close the largely unprotected border with Mexico, a large number of troops were kept on the border until the Mexican political situation smoothed out in 1920. A few regiments of regulars, among them The Old Guard, provided a disciplined backbone and cadre of men who trained citizen soldiers for warfare in Europe. Levied several times for men to fill up infantry units ordered overseas, by the end of the war and the occupation duty on the Rhine in 1921, almost every man in the Regiment in 1916 had been ordered overseas. In the Regiment at this time–and destined to rotate through and serve in Europe–were several young officers who were later to become famous: including James A. Van Fleet, later Field Commander in Korea; Henry H. Arnold, Army Air Force Chief of Staff during WWII; and Matthew B. Ridgway, Chief of Staff of the Army during the 1950’s.

At the end of the Mexican Border mission, the Regiment was ordered for a short time to Camp Sherman, Ohio, and then to Camp Perry, Ohio. The national rifle matches had been held there for many years, and in 1921, as in previous years, The Old Guard provided a cadre to garrison the post and conduct the matches. In August 1921, the Regiment was ordered to Fort Snelling, their old home, not seen for twenty years. In the post-war reductions of the army’s budget, all funds were limited, and no transportation was available to move the Regiment. Undaunted, they marched.

Leaving Camp Perry in September 1921, the Regiment marched by road to Fort Sheridan, Illinois, and then to Fort Snelling in November. The snows started early, and the 940-mile exercise was not without incident. The Regiment became acclimatized in this way to its old home in Minnesota and its old mission. This mission to be taken up when the regimental commander found that cold weather equipment, including skis, snowshoes, and sled mounts for machine guns had been turned-in by units recently stationed in North Russia. The Regiment settled into a twenty-year peacetime mission of training National Guard and Reserve troops from the surrounding states and in the local camp of the Civilian Military Training Corps. For a few weeks a year, these men began to get some military training and a basic introduction to military life. The program was particularly important during the Great Depression, as it provided a structured life, with some pay, for men not otherwise employed.

Hard Times and World War

At the beginning of the period, in the early 1920’s, the Army fell on hard times. Having just fought–and, Americans thought, won–the Great War, a wave of anti-military feeling swept over the nation. Disarmament, a wrenching reduction in force for all services, and the drastic shrinkage of budgets for the armed services brought poor morale, unit cohesion problems, and a decline in re-enlistments. The Army sought ways to solve the problems within the constraints imposed.

One way was to use the unique cold weather mission of the Old Guard as an inducement. Sports became more important, and men were sought who could ski, and had cold weather survival skills. Another inducement was an increased Army-wide emphasis on lineage and honors, unit history, and heraldry. The creation of divisional and other unit shoulder sleeve insignia in Europe during WWI had been successful, and the inevitable result was the demand for distinctive insignia for units at lower levels in the Army. In 1922, the Army Adjutant General received from all regiments in the Army, the requests for a distinctive unit insignia for each. That for the 3rd Infantry was based on a story that during the earliest days of the Regiment, the men had taken strips of buff colored rawhide and woven them into their black knapsack straps as a distinctive sign. The story is probably apocryphal, but was accepted and is the basis for the adoption of the “Buff Strap,” or “Knapsack Strap,” as the Regiment’s Distinctive Unit Trimming was originally called. The cocked hat insignia, originally used to fasten the strap to the epaulet at the top of the shoulder, was not authorized (the Adjutant General was silent as to how the “Knapsack Strap” was to be fastened). The cocked hat insignia was forbidden from being worn at least once. The Adjutant General was in Washington, but the Regiment was not. The insignia, which came to be called a “Cockade,” continued to be worn until finally officially approved in 1959.

The Second Great War

What became the Second World War began in Europe in September 1939. In the United States, the administration and the armed services come to believe that if we did not help our allies in Europe, we would eventually have to fight the fascists by ourselves. In 1940, at the time of the London Blitz and the German U-Boat war, the United States began to negotiate a trade. In return for First World War vintage destroyers, the British gave the US use of sites for overseas bases from which troops began a forward defense. Because a declared state of war did not exist between the United States and any other country, the President had limited options in his decision over how to garrison the new bases. Limited to the Regular Army, he chose the best trained men for cold weather operations for the northern bases. The 3rd Battalion, 3rd Infantry left Fort Snelling for Newfoundland, one of the first American units shipped out of the country in anticipation of our defense of the country against Germany and our entrance into the Second World War. The unit’s post was Fort Pepperell, one of the northernmost outposts in the North American security cordon. While the post was being built in the summer of 1941, the Regiment lived aboard an Army transport, the US Army Transport Edmund B. Alexander, named after the Mexican War commander of the Regiment. The rest of the Regiment moved to Newfoundland eventually and one battalion even moved to Greenland for a time. The unit’s mission was to protect the port of St. John’s, and help defend the area against raids, all part of a continental defense perimeter set up as a precaution against enemy invasion or enemy intelligence gathering. The area was on the North Atlantic convoy routes to England and Russia, and Newfoundland was used to ferry aircraft from American factories to the front in Europe. The duty was cold, wet, thankless, and absolutely necessary.

By 1943, the menace of the German U-Boats had begun to diminish, and the 3rd, after almost three years overseas, rotated to the United States. Stationed at Camp Butner in North Carolina and in Georgia at Fort Benning, the unit reverted to one of its traditional roles, that of training other troops. For a time, the 3rd Infantry became the demonstration troops at the Infantry School, teaching men by example in the course of instruction at the Infantry Officer’s Candidate School. In the winter of 1944, the course of the war in Europe changed the Regiment’s duty abruptly.

The December 1944 German offensive in the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge, resulted in The Old Guard being sent to the European Theater of Operations. The 3rd Infantry Regiment arrived in France in March 1945 and was assigned to the 106th Infantry Division. The 106th had lost two of its infantry regiments in the Battle of the Bulge. April 7, 1945 found The Old Guard encamped on an airfield outside the city of Rennes, France on the Brittany peninsula. The men of The Old Guard began to learn first-hand about war in Europe by training near the front lines around the besieged German-held French ports of St. Nazaire and Lorient. In addition to their training, The Old Guard was placed in direct support to the 66th Infantry Division, the US unit with the mission of holding in the enemy. An attempted German breakout from St. Nazaire put The Old Guard on alert, but orders to move never came. The 3rd Infantry earned the NORTHERN FRANCE streamer for their participation in this campaign. From Rennes, the 3rd moved to Germany, near Mainz in late April 1945.

The war was not over, but the great increase in the numbers of prisoners of war and refugees was seriously slowing the advance of the American armies. The 106th Division was chosen to handle the influx of prisoners. The Old Guard was given responsibility for camps at Buderich, Limburg, Budesheim, Ditersheim, Mainz, Siershan, Lagstadt, Hergeshausen, Babenhausen, Rheydt, Darmstadt, and others. Literally hundreds of thousands of German prisoners and Russian former prisoners were fed, clothed, medicated, interrogated, classified, and released after April 1945. In the following year, the 3rd also assumed responsibility for all Civilian Internee camps in the 7th Army area, a staggering 19 installations, holding 50,000 people, including hospitals, Friendly Witness Barracks, and SS prisoner compounds. In all, The Old Guard administered, fed, clothed, and guarded or protected 1,050,000 people in camps scattered over a large part of Germany for a year.

On the April 9, 1946, the 81st anniversary of the Old Guard’s witnessing the surrender at Appomattox, the unit moved to Berlin to become part of the occupying forces of that capital. Staying until November, the unit was relieved by the 16th Infantry and was, for the first time, inactivated. Caught in the post-war demobilization, The Old Guard’s colors and records were sent back to the United States on November 20, 1946.

A Colder War and Vietnam

On 6 April 1948, the 3rd Infantry Regiment was reactivated on the Capital Plaza in Washington, DC. What came to be known as the “Cold War” created a need for greater protection of the capital, national leaders, and public property. It was decided that The Old Guard, as the oldest active Infantry regiment, would be the ideal choice. The mission to protect the capital had been performed by Military Policemen of the 703rd and the 712th MP Battalions since the end of the World War 2. The men of the 703rd were transferred to the lst Battalion, 3rd Infantry, and those in the 712th became the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry, with a large number of recruit trainees from Fort Dix, New Jersey added to both battalions. The Military District of Washington’s (MDW) ceremonial mission had been performed since 1943 by the MDW Ceremonial Detachment. The Detachment became Company A of The Old Guard, beginning the 3rd’s ceremonial mission in the capital. With the addition of the Ceremonial Detachment came the mission to perform burials in Arlington Cemetery, diplomatic arrivals and departures, the perpetual guard at the Tomb, as well caissons, horses and salute guns. The 3rd Infantry Regiment brought its own traditional color guard dressed in Revolutionary War style uniforms.

The Old Guard had an interest in its history for most of the 19th century, and has maintained a Regimental collection of artifacts, uniforms, flags, and documents since before the Civil War. World War 2 almost caused their loss. When the last elements of the Regiment left Fort Snelling in 1942, this collection was put for safekeeping at the Minnesota Historical Society at St. Paul. With the reactivation of the Regiment in 1948, there were no members of the unit with any knowledge of the past history of the Regiment, or the Regimental collection. Until 1950 or 1951, the Regiment’s physical ties with its past remained lost. A single exception was a photograph found of the Chapultepec Baton, and a replica (not to scale) made with materials from a White House renovation, presented to the Regiment by President Truman. The assignment of Master Sergeant Jack Watts to the Regiment at Fort Myer saved the collection. Watts, who had soldiered in the 3rd before the war, remembered the items exhibited at Fort Snelling, and asked the commander, Colonel William W. Jenna, where they were. Jenna sent Watts to Fort Snelling to look for the collection, which was eventually located and returned to The Old Guard. This collection, one of the few regimental collections in the Army, formed the nucleus of The Old Guard Museum when it was begun in 1957.

For a time during the Korean War, The Old Guard was severely hampered by the constant rotation of infantry troops from the United States to units based in Korea. Company H, which was then a provisional company of basic trainees being groomed for the ceremonial duties of The Old Guard, was shipped out of Fort Myer almost immediately after graduation in 1951. These men served as replacements in the Eighth Army in Korea and did not return to their Old Guard duties. During this period the development of the changing of the guard at the Tomb from a simple guard mount to a more formalized, ritualized ceremony took place, as did the integration of the Army and The Old Guard. The first black soldier became an Old Guardsman in 1953. In 1961, Specialist Four Fred Moore became the first black Tomb Guard.

Since 1948, the Regiment has been reorganized several times, becoming Battle Groups, a series of autonomous battalions, and reduced eventually to a single reinforced battalion. In a 1957 Army-wide reorganization under the Pentomic concept, the functional regimental system under which The Old Guard had been created in 1784 ended with the adoption of the Combat Arms Regimental System. Thereafter, there would be no separate regimental headquarters, but only unrelated units having the same lineage and honors. The pre-1957 Regimental organic companies provided the lineal basis for each new unit. Company A of the Regiment became the Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) for 1st Battle Group, 3rd Infantry at Forts Myer and McNair. Old Company B became HHC 2nd Battle Group, 3rd Infantry activated in Korea as part of the 7th Infantry Division. New lettered companies were activated for the new Battle Groups. The Pentomic concept was soon replaced by ROAD (Reorganization Objective Army Divisions). The battle group was dropped in favor of the battalion as the basic tactical and administrative unit of the infantry. In 1963, 2nd Battle Group, 3rd Infantry was inactivated in Korea and 1st Battle Group in Washington, DC became 1st Battalion. The 3rd Battalion, in recent times a US Army Reserve (USAR) unit in the Regiment’s old home at Fort Snelling, was activated in 1959 as the 3rd Battle Group, 3rd Infantry and inactivated in August 1994. It was assigned first to the 103rd Infantry Division and later to the 205th Infantry Brigade, both of the USAR. With the widening of the war in Vietnam, a new 2nd, and a 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th Battalions were activated. All of these were autonomous, having a separate command and staff from the 1st Battalion at Fort Myer, and never serving under a single regimental headquarters. In December 1973, the Regiment was withdrawn from CARS and reorganized under the US Army Regimental System.

In 1966, the 2nd and 4th Battalions were activated, the 2nd in June at Fort Benning and the 4th in July at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. The 2nd Battalion was assigned to the 199th Infantry Brigade, eventually serving in the area around Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). The 4th Battalion served in the 11th Infantry Brigade and then the 198th Infantry Brigade of the Americal Division in the I Corps area near the northern border of South Vietnam. Both battalions were inactivated by November 1971. Neither battalion was very much aware of the other’s existence in Vietnam, but both, at various times, requested the assistance of the 1st Battalion at Fort Myer in providing histories of The Old Guard and other information and in one instance, replica Continental Army uniforms. In their four year existence, both battalions were decorated, the 2nd receiving a Valorous Unit Award and the 4th’s Company E Reconnaissance Platoon receiving a Presidential Unit Citation. Corporal Michael F. Folland, of the 2nd Battalion, was awarded a Medal of Honor posthumously for his actions in Vietnam. The 5th, 6th, and 7th Battalions were elements of the 6th Infantry Division constituted at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in November 1967 and were all inactivated by July 1969.

Tactical and Ceremonial

In conflicts (and most larger operations) since the Vietnam War, The Old Guard has been levied for soldiers to serve in units overseas, often troops with a specialty needed desperately during a deployment. These soldiers served not as Old Guardsmen, (since the unit is not deployed) but with other units. Proficiency in infantry skills and the other military occupational specialties of Old Guard soldiers as well as the battalion’s readiness to perform it’s tactical mission as a unit have always been part of The Old Guard’s mandate.

The requirement for the Old Guard to represent all of the Army, regardless of sex or race, has created special circumstances and solutions in the unit in the past, and will again. Although women had been attached to The Old Guard for ceremonial purposes from Headquarters Company, US Army in the 1980’s and women joined the Old Guard’s Fife and Drum Corps in 1982, the first wide-ranging permanent assignment of women to the unit in 1994 required an unusual, historically based solution to the question of how to have women serve. Because of its mission as light infantry, The Old Guard is legally prohibited from directly having women soldiers in the line companies, who would be subject to ground combat if deployed. Because of its ceremonial status as representing all of the Army, it must take a visible role in representing all soldiers. The solution to this paradox lay in attaching a re-activated, decorated Military Police Company to The Old Guard. Activated and attached as part of the Regiment on November 1st, 1994, the 289th Military Police Company and its soldiers of both genders are fully integrated into the Army’s oldest regiment. In 1996, Sergeant Heather Johnsen of the 289th Military Police Company became the first female soldier to earn the Tomb Guard Identification Badge.

The 1st Battalion, 3rd Infantry (The Old Guard) at Fort Myer, Virginia and Fort McNair, DC is a unique unit, there being no other in the world like it. Although most nations have units in their armed services that perform ceremonial duties, none has the mix of missions peculiar to The Old Guard. Its parts have grown and developed over the last fifty years to provide capabilities unknown elsewhere. It is the only US Army unit to have official historic uniforms; the only to have its own field music; and the only to have and use horses in performance of its official duties. Since 1948, Old Guard soldiers have guarded the Tomb of the Unknowns. The unit’s traditional costumed color guard evolved into the Continental Color Guard. Drill teams had existed within the 3rd Infantry, and finally The US Army Drill Team was organized as part of The Old Guard in 1957. The Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps was organized in 1960 and became a company of the battalion in 1995. In December 1973, a recreated version of General George Washington’s Commander-in-Chief’s Guard was organized from Company A. Trained, dressed and equipped as their Revolutionary War forbearers had been, this unit went from a Bicentennial of the US project to become a permanent and very popular part of The Old Guard. While the 1st Battalion, 3rd Infantry (The Old Guard) is not the only military unit to support government operations in the capital, it is the lead element of the leading service.

The 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry (The Old Guard) was reactivated March 16, 2001, at Ft. Lewis, Washington as part of the 3rd Brigade of the 2nd Infantry Division. This unit is the Army’s first Stryker Brigade Combat Team (SBCT). The 2nd Battalion of The Old Guard is one three infantry battalions in the SBCT. These infantry battalions are the principle fighting force of the SBCT and the new Stryker vehicles are the SBCT’s primary combat and combat support platforms. Part of the Army Transformation, the Stryker Brigade is capable of conducting a range of military operations from low through high intensity combat operations. It is a rapidly deployable force with significant firepower. The battalion chose “Patriots” as their nickname and call sign.

A New Kind of War in a New Millennium

On September 11, 2001, the soldiers of the 1st Battalion of The Old Guard responded to the most devastating attack on the nation in our history. Two hijacked airliners were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, causing their collapse. A third airliner was plunged into The Pentagon and a fourth aircraft, thought to be headed on a suicide mission to Washington, DC crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after its passengers attempted to regain control from the hijackers. Not since Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 has the United States been attacked with such devastating results.

Soldiers of the 1st Battalion, 3rd Infantry (The Old Guard) from Fort Myer, adjacent to The Pentagon were able to hear and some even witnessed the airliner plowing into the building. The crash was also heard by the soldiers of Company A at Fort McNair across the Potomac River in Washington, DC. The response from The Old Guard was immediate by the troops at both posts. Long-studied contingency plans and hastily prepared on-the-spot plans went into effect. The soldiers assembled and prepared for their varied missions with calm professionalism under the confident leadership of their officers and noncommissioned officers and were among the first to arrive on the scene of the attack. Whether they performed force protection duties, conducted search and rescue/recovery missions at The Pentagon attack site or provided communications, medical and other support, the performance of every member of the unit added to the proud heritage of the Regiment. This description is from a U.S. Army news report:

“The soldiers wore face shields, protective breathing masks and white biological protection garments…Dust and soot covered their yellow protective boots. And they faced the grim task of sifting through the rubble to recover the remains of victims.”

For several months after the attack, in addition to its ceremonial duties, The Old Guard was heavily tasked in support of Operation Noble Eagle, the domestic military operation initiated to facilitate homeland defense in the new Global War on Terrorism in which the country was now involved. Participation in other operations followed — Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom.

The soldiers of the 2d Battalion deployed to Iraq from Fort Lewis, Washington in November 2003. The 2d Battalion was part of the 3d Brigade, 2d Infantry Division. That brigade was the first Stryker Brigade to deploy in combat. The Stryker is an eight-wheeled light-armored fighting vehicle. The 3d Brigade redeployed back to Fort Lewis in October 2004, replaced by the 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry Division.

In December 2003, Company B, 1st Battalion deployed in support of Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA). Stationed at Camp Lemonier, Djibouti, Company B conducted training with the Djiboutian military, provided humanitarian relief during the April 2004 floods, constructed drinking wells, created roads and a portion of the company trained aboard the US Navy’s USS Wasp for two months with U.S. Marines. The company came under Central Command (CENTCOM) during the deployment. Over the course of deployment the company conducted missions in the neighboring nations of Ethiopia and Kenya. All of Company B returned to Fort Myer by the end of July 2004. This was the first deployment of a 1st Battalion element since World War II. In the months leading up to the deployment, Company B trained at Fort A.P. Hill, VA and Fort Polk, LA.

In the course of B Company’s deployment, former President Ronald Reagan died after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease at his California home on June 5, 2004. A joint honor guard team traveled to California, where the President Reagan laid in state at the Reagan Presidential Library. The vigil at the library saw 2,000 mourners an hour pay their respects from June 7-9. On June 9, the president’s body was flown to Andrews Air Force Base and then the procession made its way to the Capitol. The last leg of the route along Constitution Avenue, from the White House to the Capitol, saw his remains transferred to a caisson and escorted by a joint service honor guard. At the time of the transfer from the hearse to the caisson, the Presidential Salute Battery fired a 21-gun salute. The former president laid in state in the Capitol Rotunda from June 9-11. The State Funeral continued with a procession from Capitol Hill to Washington National Cathedral for a funeral service. In attendance was President George W. Bush, along with all of the living former presidents and large number of former and present-day world leaders. After the funeral service, the president’s body was transported to Andrews Air Force Base and then to Reagan Presidential Library, where he would be interred on June 11.

In the first half of 2004, elements of the Old Guard stationed in the National Capital Region began its largest reorganization since 1957. The reorganized elements more closely resembled the unit structure during the period from 1948-1957. A separate Regimental Headquarters Company was activated, separate from 1st Battalion’s existing Headquarters Company. At the end of 2008, the 4th Battalion was reactivated in a ceremony attended by a contingent of veterans who served with the 4th Battalion in Vietnam. Companies within the former 1st Battalion were reshuffled between the 1st and 4th Battalions.

The end result saw 1st Battalion organized with the Headquarters Company and the “line companies” of Companies B, C, D, and H. The Headquarters Company of 1st Battalion incorporated the Caisson Platoon and the Presidential Salute Battery.

The 4th Battalion consisted of the Headquarters Company along with units were associated with ceremonial duties and specialized missions – the 289th Military Police Company (plus the 947th Military Police Detachment), the 529th Regimental Support Company (RSC), Company A (Commander-in-Chief’s Guard), Company E (Honor Guard), and the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps.The Tomb Sentinels and the U.S. Army Drill Team fell under Headquarters Company, 4th Battalion. The Continental Color Guard remained part of Honor Guard Company. The 529th RSC provided support for both battalions in the areas of food service, maintenance, transportation, medical and munitions support. The 947th Military Police Detachment augmented the 289th by adding military working dogs for bomb detection in support of government officials and visiting dignitaries at high-visibility events. During this transition period, the Fort Myer Military Police Company inactivated on August 15, 2004 with the members integrated into the 289th Military Police Company.

Caisson Platoon farrier Pete Cote retired from Federal service in May 2005. Cote served as the farrier since 1971. He served as farrier while on active-duty the previous year and then transitioned to a civilian employee for the remainder of his career. Cote served as farrier through nine presidential inaugurations during his thirty-four years of civilian service while enduring a multitude of on-the-job injuries including a collapsed lung, cracked ribs, and a reconstructed nose from a head-butt delivered by a horse.

In early summer 2006, the 2d Battalion of the Old Guard deployed to Iraq for a second time, returning to Mosul, where the unit saw action during its previous deployment. At the end of 2006, the 3d Brigade moved from Mosul to Baghdad, serving as a strike force for the US commanders located in the capital. During this second phase of the deployment, the 3d Brigade launched “Arrowhead Ripper” in Diyala against al-Qaeda insurgents in Baqubah. Some elements of the 2d Battalion were attached to the 4th Infantry Brigade, 1st Infantry Division in the sieges in and around Baghdad. Soldiers encountered buried bombs and 38 booby-trapped houses. The brigade returned to Fort Lewis in the fall of 2007.

The day after Christmas 2006, news broke that former President Gerald R. Ford died at his California home, at the age of 93. The State Funeral that followed was a much more subdued event than President Reagan’s funeral two years prior. The State Funeral events started on December 29, with a service in California and then events shifted to Washington, DC on December 30. The remains of President Ford arrived at Andrews Air Force Base that evening. The procession made its way to the U.S. Capitol taking a route that honored the sites associated with Ford’s life and career. President Ford’s remains laid in state at the Capitol from December 30 until January 2, 2007. On January 2, a service was held at National Cathedral and that evening his remains were transported to Grand Rapids, MI. Ford was interred the next day at the Ford Presidential Library. Elements of the Old Guard and MDW were involved in all elements of the State Funeral.

A second element of 1st Battalion deployed in support of the Global War on Terror under the Combined Joint Task Force-horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) in March 2007. Company D deployed for 15 months and, like Company B in 2004, was based out of Camp Lemonier, Djibouti. The company was spread at times across neighboring nations providing training and assistance to coalition forces. Members of the company trained at the Desert and Survival French Commando Course, explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) training, and alongside Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 464. Company D returned to Fort Myer in June 2008.

The Department of Defense announced upcoming changes to regulations concerning full honor burials in March 2007. Effective January 1, 2009, service members killed in action were eligible to be buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery. The first service member laid to rest under the new regulations was Specialist Joseph M. Hernandez, who was killed in action January 9, in Zabul Province, Afghanistan. SPC Hernandez was a former member of the Old Guard (Company A) and was laid to rest by members of his former unit with full honors.

At the beginning of 2009, another link to the unit’s past was lost. Retired Master Sergeant William Daniel died January 10, 2009. MSG Daniel was the first soldier awarded the Tomb Guard Identification Badge in 1958. He donated Tomb Badge #1 to the Army in 1996, after which it was placed on display at the Tomb Quarters. He was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery on February 11.

Every four years the Regiment is placed in the limelight when it acts as the lead element in the presidential inaugurations. The stage was even bigger as Barack Obama, the nation’s first African-American president, was sworn into office on January 20, 2009. The events were watched around the world and throughout the coverage members of the Old Guard were featured prominently during television coverage.

In August 2009, the 2d Battalion deployed again. This deployment to the Diyala Province, Iraq was again as part of 3d Brigade, 2d Infantry Division. This was the third deployment of the 2d Battalion since 2001. This one-year deployment saw the unit partner with Iraqi security forces and close down American facilities as the war came to a close. The 2d Battalion returned to Joint Base Lewis-McChord in July 2010.

One month the deployment of 2d Battalion, soldiers of Company C, 1st Battalion became the third company-sized deployment of 1st Battalion in support of the Global War on Terrorism. The company deployed to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The company arrived at Camp Taji where it was responsible for one of three remaining Iraqi prisons, which held about 300 detainees. The company started to conduct combat patrols in the Combined Area of Operations Dakotas on the northern perimeter of Contingency Operation Base (COB) Taji in February 2010. Part of the company provided security for the Spring 2010 parliamentary elections. The patrols ended in July, with the company having completed 180 combat patrols, 15 counter improvised explosive device (IED) missions and one Joint Iraqi-US Army mission. Their last combat patrol was conducted on July 1, and one month later the company deployed back to Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall.

The Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps celebrated fifty years of service in 2010. The Fife and Drum Corps has participated in every Presidential Inauguration since the 1961 Inauguration of John F. Kennedy. The Corps was recognized for its service with the Army Superior Unit Award. The celebrations continued all year, with a 50th Anniversary Muster Tour and in June hosted the 50th Anniversary Tattoo at Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall. The event that featured the “The Commandant’s Own” U.S. Marine Drum and Bugle Corps, the West Point Military Academy Band “Hellcats,” the Fifes and Drums of Colonial Williamsburg, the City of Washington Pipe Band, among others.